We all crave recognition. Studies by Harvard psychologist David McClelland show that the need for achievement, affiliation (connection with others), and power are core human motivators. Compliments tick all these boxes, validating our efforts, strengthening bonds, and boosting self-esteem. Yet, a strange phenomenon occurs – we often fumble when giving or receiving compliments. Why is something so seemingly positive shrouded in awkwardness? Here are 12 surprising reasons, backed by research and psychology, that explain our complimenting conundrum:

Feeling Like a Fraud? You Might Downplay Compliments

Credit: iStockphoto

A 2017 study by The Journal of Personality and Social Psychology found that people with high levels of imposter syndrome, the feeling of being a fraud despite accomplishments, often downplay compliments. They might deflect praise with "It was nothing" or "Anyone could have done it," diminishing their own hard work.

Introverts May Prefer Quieter Praise

Credit: iStockphoto

Introverts, or those who recharge alone, may find compliments thrusting them into an uncomfortable spotlight. A 2012 study in the journal Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin suggests introverts often prefer recognition in smaller, more intimate settings. A quiet "thank you" might be their way of deflecting unwanted attention.

Different Cultures Have Different Compliment Styles

Credit: iStockphoto

Cultures differ in their comfort level with compliments. A study published in the Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology found that cultures like the United States tend to be more expressive with praise, while collectivist cultures like Japan may view excessive compliments as boastful.

Women Often Praise Others But Downplay Their Own Wins

Credit: iStockphoto

Research from Harvard Business Review shows that women are less likely to give themselves credit and more likely to offer praise to others. This "cheerleader effect" might explain why women sometimes downplay compliments they receive.

We Suspect Insincere Compliments

Credit: iStockphoto

A 2019 University of California, Berkeley study suggests we're more suspicious of insincere compliments. A backhanded compliment like "That dress is interesting...on you" can leave us wondering about the giver's true intent.

Perfectionists Might See Compliments as Falling Short

Credit: iStockphoto

Perfectionists often hold themselves to impossibly high standards. A 2018 study in Personality and Individual Differences suggests they might view compliments as falling short of their own expectations, leading to a sense of disappointment rather than pride.

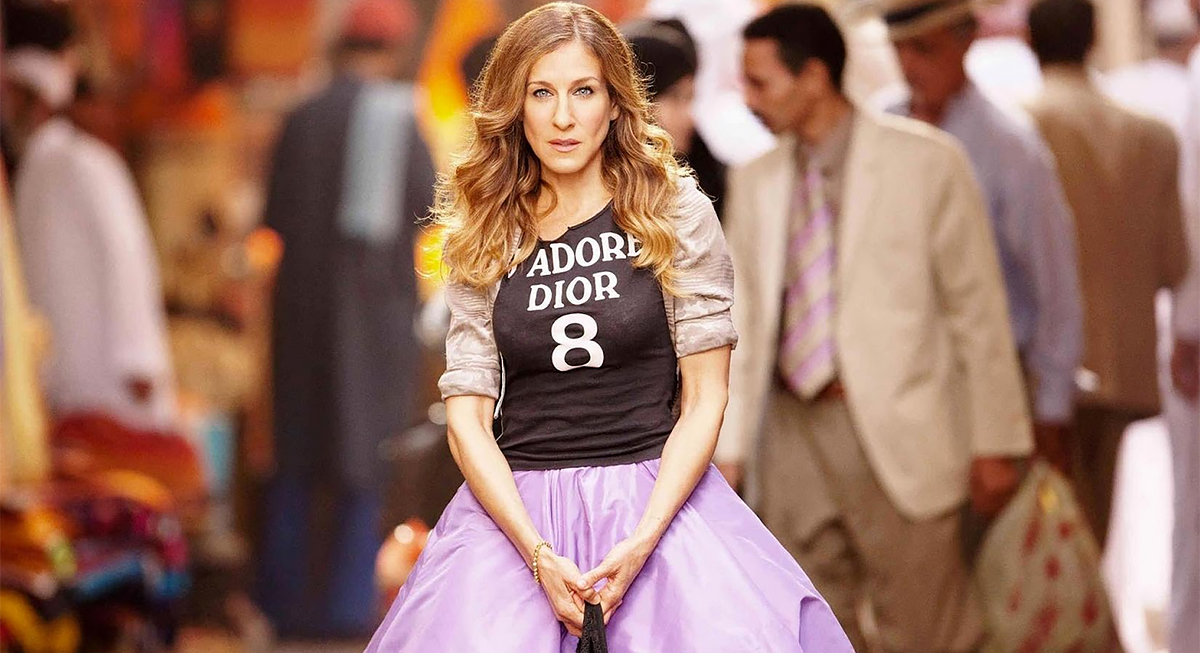

Saying "This Old Thing?" Can Come Off as Ungrateful

Credit: iStockphoto

The subtle art of bragging disguised as humility can backfire. Saying "This old thing?" in response to a compliment might make you seem ungrateful or insecure.

Bragging Excessively Might Make Compliments Feel Unearned

Credit: iStockphoto

People who brag excessively might struggle to receive compliments genuinely. A 2015 study in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology suggests that chronic braggarts might be seen as less deserving of praise, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Low Self-Esteem Can Make Compliments Hard to Believe

Credit: iStockphoto

People with low self-esteem might struggle to believe in compliments. A 2016 study in Psychological Science suggests they may question the giver's motives or dismiss the praise altogether.

Social Media Can Make Us Feel Like Compliments Don't Apply to Us

Credit: freepik

Social media's highlight reel can distort our perception of reality. A 2018 Pew Research Center survey found that comparing ourselves to others online can lead to feelings of inadequacy. A compliment might trigger this comparison, making us feel we don't deserve the praise.

A Lack of Childhood Praise Can Make Compliments Feel Alien

Credit: freepik

If you rarely received compliments as a child, you might struggle to accept them as an adult. A 2017 study in Child Development found that a lack of praise in early life can hinder a person's ability to internalize positive feedback.

A Compliment Might Reinforce Stereotypes Unintentionally

Credit: iStockphoto

A seemingly innocent compliment can become a microaggression if it reinforces stereotypes. For example, praising a woman for her "strength" in a traditionally male-dominated field might unintentionally imply that weakness is the norm.