50 Brand Names We All Use as Everyday Words

You’ve probably used a brand name thinking it was the actual tag for the thing itself, because everyone does. When one label becomes the word for an entire product category, it’s marketing gold and a legal headache. These cases show what happens when a brand becomes so big that it loses its name to the masses.

Jet Ski

Credit: Canva

Next time you’re zipping across the lake on what everyone calls a “Jet Ski,” flip it over and check the label. If it wasn’t made by Kawasaki Heavy Industries, it’s a personal watercraft. It got popular in the 1970s, and now people slap it on everything, including Sea-Doos and Yamahas. Kawasaki’s trademark lawyers aren’t thrilled.

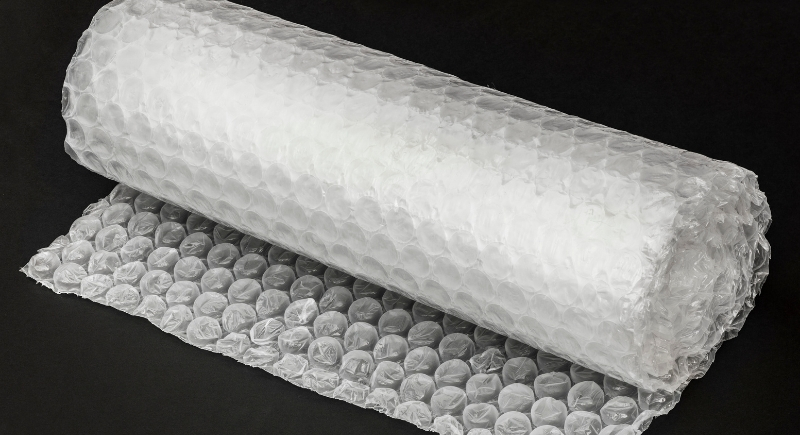

Bubble Wrap

Credit: Getty Images

Unless it says Sealed Air Corporation on the box, you’re squeezing air bubbles, not Bubble Wrap. That name got trademarked. People now call any cushioned plastic packaging “bubble wrap,” which makes patenting tricky. Still, everyone knows what you mean.

Onesies

Credit: Getty Images

You’ve probably called every baby bodysuit a “onesie” at some point, but Gerber Childrenswear owns that word—and they don’t play. Only their products can legally wear the title. Everyone else is selling “bodysuits.” Gerber also owns “Twosies” and “Funzies,” too.

Jacuzzi

Credit: Getty Images

Unless that tub was made by Jacuzzi Inc., you’re lounging in a hot tub—full stop. The company introduced whirlpool baths in 1949, and their name stuck like bath foam. Now it’s used generically, despite their efforts to keep it exclusive.

Crock-Pot

Credit: Getty Images

Every slow-cooking chili on the counter is probably called a Crock-Pot, even if it’s not one. Sunbeam Products owns that brand name, but it’s become America’s shorthand for any slow cooker. In the UK, however, people tend to use the term “slow cooker.”

Fluffernutter

Credit: Getty Images

Say “Fluffernutter,” and New Englanders immediately picture a gooey peanut butter and marshmallow sandwich. But that nostalgic term is a registered label of Durkee-Mower, makers of Marshmallow Fluff. It’s delicious, trademarked, and a little legally messy.

Seeing Eye Dog

Credit: pixelshot

Unless that guide dog was trained by The Seeing Eye in Morristown, New Jersey, it’s not a Seeing Eye dog but a guide dog. That trademark dates back to 1929, and the nonprofit fiercely defends it. However, in casual speech, most folks don’t make the distinction.

Breathalyzer

Credit: Canva

Blow into any alcohol-testing device and someone will call it a “Breathalyzer,” even if it’s not the real deal. That name belongs to the Indiana University Foundation, born from a device developed in 1931. Its early dominance made the term unavoidable. Now it describes every breath test gadget, especially in cop shows.

Zamboni

Credit: pexels

Watch ice get smoothed between hockey periods, and someone’s bound to shout, “Here comes the Zamboni!” That machine might not be a Zamboni at all. Only the Zamboni Company makes real ones, named after inventor Frank Zamboni. The name has become universal for any ice resurfacer, even if it came from somewhere else entirely.

ChapStick

Credit: Canva

You dig into your pocket for lip balm, and someone says, “Got any ChapStick?” Whether it’s Burt’s Bees, Carmex, or a no-name brand, the label doesn’t seem to matter. ChapStick, owned by Pfizer, was one of the first, and the name stuck—literally and linguistically.

Kleenex

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Someone sneezes and asks for a Kleenex, but you hand them store-brand tissues. Doesn’t matter—they still say thanks for the “Kleenex.” Kimberly-Clark owns the name, but it’s used for every facial tissue on the planet. The brand’s marketing in the 1920s was so strong that dictionaries now list it as a common term.

Ping-Pong

Credit: Getty Images

Let the paddles fly, but remember—unless you’re playing with official gear, it’s not Ping-Pong but table tennis. The term was trademarked in 1901 and sold to Parker Brothers, but players now casually use it for all versions of the game. Even the International Table Tennis Federation had to go with the more neutral name.

Popsicle

Credit: Getty Images

Frank Epperson accidentally created this frozen treat in 1905, and the name Popsicle, now owned by Unilever, became iconic. Despite the trademark, people use it generically for any frozen treat on a stick. Unilever suggests calling them “ice pops” or “freezer pops” unless it’s officially their product, but most folks stick with Popsicle.

Q-Tips

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Originally called Baby Gays, these cotton swabs were renamed Q-Tips in 1926—the “Q” stands for quality. Now owned by Unilever, the name is widely misused to describe any cotton swab. People rarely ask for cotton swabs—they ask for Q-Tips.

Rollerblade

Credit: Canva

Brothers Scott and Brennan Olson launched Rollerblade in 1979, and it dominated the inline skate market. Because it was the only brand for years, people started using “rollerblade” for all inline skates. The name is still a trademark, but in everyday speech, it’s nearly impossible to separate the brand from the product.

Scotch Tape

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Scotch Tape, invented by a 3M engineer in 1930, became a household staple. The name was inspired by a complaint about sticky adhesive. Today, many call any transparent adhesive tape “Scotch Tape,” even if it’s another brand. The correct generic term is “cellophane tape,” but that rarely sticks in everyday conversation.

Sharpie

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

The first pen-style permanent marker hit shelves in 1964 under the Sharpie brand. Now owned by Newell Brands, it’s often used generically to describe any permanent marker. Despite being a registered trademark, people say, “pass me a Sharpie,” regardless of the brand.

Realtor

Credit: Getty Images

The term “Realtor” is trademarked by the National Association of Realtors and should only apply to NAR members. Many use it generically to refer to any real estate agent. While the brand is enforced, misuse persists and continues to blur the line between licensed Realtors and general real estate professionals.

Tupperware

Credit: pixelshot

Earle Tupper’s airtight containers became a sensation in mid-century America, and the name Tupperware stuck hard. It’s a trademark, but people use it to describe any plastic food storage container. Its dominance in homes and parties helped genericize the name, even though only products made by the brand are true Tupperware.

Velcro

Credit: Getty Images

Velcro was inspired by burrs sticking to dog fur and became the leading brand of hook-and-loop fasteners. Although Velcro Companies owns the label, the word is now widely used generically. They’ve even launched public campaigns like “Don’t Say Velcro” to remind people that it’s not a general product name.

Weed Eater

Credit: Getty Images

The Weed Eater was invented to trim grass around trees and is trademarked by Husqvarna. Its name, a literal description, caught on fast. People today use it for all string trimmers, regardless of brand. It’s even influenced language—some say “strim” as a verb.

Wite-Out

Credit: iStockphoto

Wite-Out is BIC’s patented brand of correction fluid, but many refer to all correction products by this name. They became the catch-all term through years of dominant market presence. The actual generic name is “correction fluid,” but Wite-Out is what people ask for.

Band-Aid

Credit: Getty Images

Earle Dickson’s invention for his accident-prone wife led to Band-Aids, now owned by Johnson & Johnson. Though the proper term is adhesive bandage, people across the U.S., Canada, and beyond say Band-Aid for any small wound covering. The brand is so embedded in language that its misuse threatens the company’s legal protection.

TASER

Credit: Getty Images

The word TASER stands for Thomas A. Swift’s Electric Rifle and refers to electroshock weapons made by Axon. People often misuse it to describe all stun devices, no matter the source. This casual usage, while widespread, risks weakening its trademark. Axon continues fighting to remind users that not every stun gun qualifies.

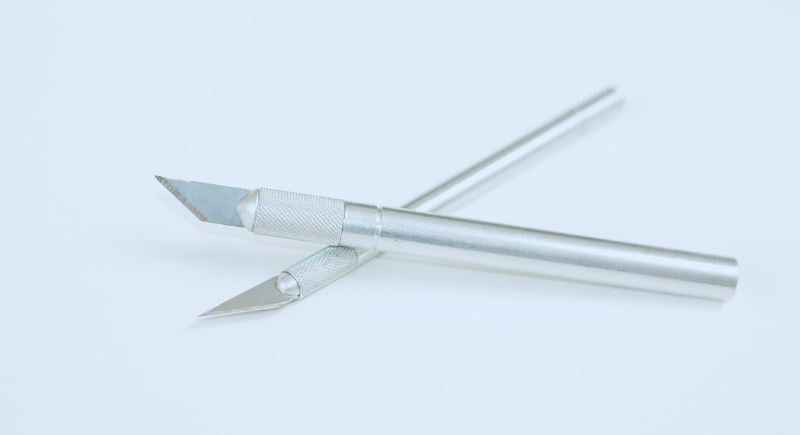

X-Acto Knife

Credit: Getty Images

Originally developed from surgical scalpels, the X-Acto knife became a go-to tool for hobbyists and artists. Today, many refer to similar tools with that brand name, regardless of who made them. Owned by Elmer’s, it’s a trademark, though the term is now often used to mean any precision craft knife.

Dumpster

Credit: Getty Images

“Dumpster” came from the Dempster Brothers in the 1930s, who combined their name with “dump.” Initially trademarked, the word became generic as people began applying it to all large waste bins. The APA even dropped the capital “D.”

Novocain

Credit: Getty Images

Although newer anesthetics like lidocaine are standard now, many still call any numbing shot “Novocain.” That’s a trademarked label for procaine hydrochloride, originally owned by Hospira. Its early dominance in dental care marked the name in everyday speech, even as the actual drug faded from regular use decades ago.

Xerox

Credit: Getty Images

Xerox became so associated with photocopying that people started using it as a verb—”to xerox”—regardless of the machine’s brand. The company has tried to stop this by urging the use of “photocopy” instead. Despite campaigns in 2010 and beyond, the word continues to appear in dictionaries and conversation as a catch-all for copies.

Post-Its

Credit: Canva

3M’s yellow sticky notes, originally called Press ‘n Peel, became Post-its after Spencer Silver’s adhesive met Art Fry’s need for bookmarks. Though the name is sealed, people call all sticky notes “Post-its.” That common misuse persists globally, even though 3M has never legally lost control of the term.

Ouija Board

Credit: Getty Images

Introduced in 1890 by Elijah Bond and now a brand of Hasbro, the Ouija Board once referred only to the original spirit-communication board. The name blends “oui” and “ja,” both meaning yes. Over time, it started being used for similar products. While Hasbro holds the rights, the term is widely generalized.

Plexiglas

Credit: Getty Images

Plexiglas is a specific acrylic product from Röhm GmbH that is commonly confused with all transparent plastic sheets. Though the generic material is polymethyl methacrylate, many call any version “Plexiglas.” That lowercase usage is so frequent that it overshadows the brand, despite competitors like Lucite and Acrylite producing nearly identical materials.

Styrofoam

Credit: Getty Images

Despite the picnic cup myth, Styrofoam is Dow Chemical’s trademark for insulation-grade polystyrene. The lightweight foam used in plates and cups is expanded polystyrene, not the real product. Still, people refer to all foam disposables as Styrofoam, even though the genuine article was never shaped into a drink container.

Formica

Credit: iStockphoto

Often used to describe any laminate countertop, Formica is a trademarked brand owned by the Letts Filofax Group. Its early market success made the name stick to all plastic surface materials. While other companies manufacture similar laminates, people continue calling them Formica—even when there’s no connection to the original brand.

Frisbee

Credit: Getty Images

Wham-O owns the Frisbee brand, but most people use it for any flying disc. Regardless of a failed legal challenge in 2010 arguing it had become generic, the term remains protected. The brand originally took off through casual beach and park play, and its widespread use blurred the lines between brand and toy.

Hula Hoop

Credit: Getty Images

Hula Hoop got sealed by Wham-O, though people now apply it to any twirling plastic ring. It became wildly popular in the 1950s and embedded itself into pop culture. As more lookalikes emerged, the name stuck generically. Though still trademarked, most don’t know the difference unless they’re reading packaging.

Slip’N Slide

Credit: Getty Images

Wham-O’s Slip’N Slide turned backyards into summer fun zones, but that name only applies to its version of the product. People now call any plastic water slide the same way, even with failed efforts in court to declare it generic. The company continues defending it along with the Frisbee and Hula Hoop brands.

Escalator

Credit: Getty Images

Otis Elevator Company coined “escalator” in 1899 to brand their moving stairs. But over time, it lost trademark status after the public adopted it generically. A court officially ruled it was no longer protected, and now every moving staircase, regardless of maker, is called an escalator.

Stetson

Credit: Getty Images

Many call any wide-brimmed cowboy hat a Stetson, but unless it’s made by the John B. Stetson Company, that’s not accurate. The brand’s popularity made the name universal in cowboy culture. The company is serious about protecting it, and even sends legal warnings when media or companies misuse the term for off-brand hats.

PowerPoint

Credit: iStockphoto

Microsoft’s PowerPoint became so dominant in presentations that its name is now often used to describe all slide deck software. Despite this common misuse, the maker holds the trademark and prefers others to say “presentation program” when not referring to their software. “PowerPoint” remains the office shorthand for any slideshow.

GED

Credit: iStockphoto

The GED trademark belongs to the American Council on Education, yet it’s become the default term for any high school equivalency test. Because of its reach and recognition, many people don’t realize it refers to a specific credential, not the entire category. ACE continues to protect the name while benefiting from its ubiquity.

Google

Credit: pixelshot

People say they “googled it,” no matter what search engine they used. Google’s legal team works to keep the domain from becoming legally generic, and courts have sided with them so far. The trademark stands, though its use as a verb for internet searches has gone global, and shows no sign of stopping.

Zipper

Credit: Getty Images

Coined by B.F. Goodrich for their sliding boot fastener in 1917, “zipper” once referred only to their product. Its sound-inspired name caught on, and over time, it lost trademark protection. Now, any fastener of that type is called a zipper, regardless of who made it—a textbook case of brand erosion.

Photoshop

Credit: Canva

People casually say they “photoshopped” an image, even if they used different software. Adobe owns the trademark and encourages users to say “edited with Adobe Photoshop.” But its popularity turned the name into shorthand for any photo manipulation.

App

Credit: pexels

While “app” sounds like a snappy abbreviation for “application,” it was once trademarked by Apple for their digital distribution platform. After a legal dispute, Apple lost exclusive rights. Today, people refer to any mobile program as an app, whether it’s from Apple’s App Store, Google Play, or a completely different platform.

AstroTurf

Credit: Canva

Originally a label of Monsanto, AstroTurf described a specific synthetic surface used in sports stadiums. As fake grass became widespread, the term began to cover all artificial turf. Even though it’s legally protected, most people don’t distinguish between brands.

Cashpoint

Credit: Getty Images

In the UK, people regularly say they’re heading to a “cashpoint,” but that term is owned by Lloyds Bank. Technically, it only applies to their ATMs. The correct generic reference is “cash machine” or “automated teller machine,” but unless someone’s in finance or legal, few make the distinction at the bank.

Cigarette Boat

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

These sleek, V-hulled speedboats get called Cigarette Boats even when they’re not made by Cigarette Racing. The name stuck due to the brand’s infamous association with smuggling in the 1970s. High speed and notoriety gave it cultural weight.

Lava Lamp

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Originally made by Mathmos, the Lava Lamp surged in popularity in the 1970s and again decades later. While the copyright is still valid, the name is used to describe all liquid motion lamps. Few realize “lava lamp” is brand-specific; most assume it applies to any glowing, swirling desktop decoration.

Filofax

Credit: Getty Images

In the 1980s, Filofax meant success, and soon came to mean any personal organizer. Owned by Letts Filofax Group, the brand name became all-inclusive through daily use. Through routine use, people began referring to all diary-style planners that way, even if they weren’t from the actual brand.

Matchbox

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Matchbox cars were originally named for their small packaging, and kids everywhere started calling any die-cast toy car a “Matchbox.” Mattel owns the brand, but the term now applies to any similar miniature vehicle.