In the years leading up to the French Revolution, the country's growing hunger went beyond the food—it was political. While commoners struggled to afford basic staples, the aristocracy lived in a world untouched by scarcity. Let’s discuss all the foods that the French elite feasted on as the rest of the nation starved—and watched.

Hot Chocolate With Orange Blossoms

Credit: flickr

Marie Antoinette started her day with a warm cup of hot chocolate flavored with orange blossom and sweet almond, made by her special chocolate maker. This rich, fragrant drink showed her elegant life, very different from the poor people outside the palace who didn't even have enough flour.

Poached Truffles

Credit: flickr

At Louis XIV's palace, Versailles, even the food was meant to be a show. The King made simple foods seem royal. Truffles, once seen as common food, were made fancy by adding them to chestnut soup and putting them in rice salads with langoustines.

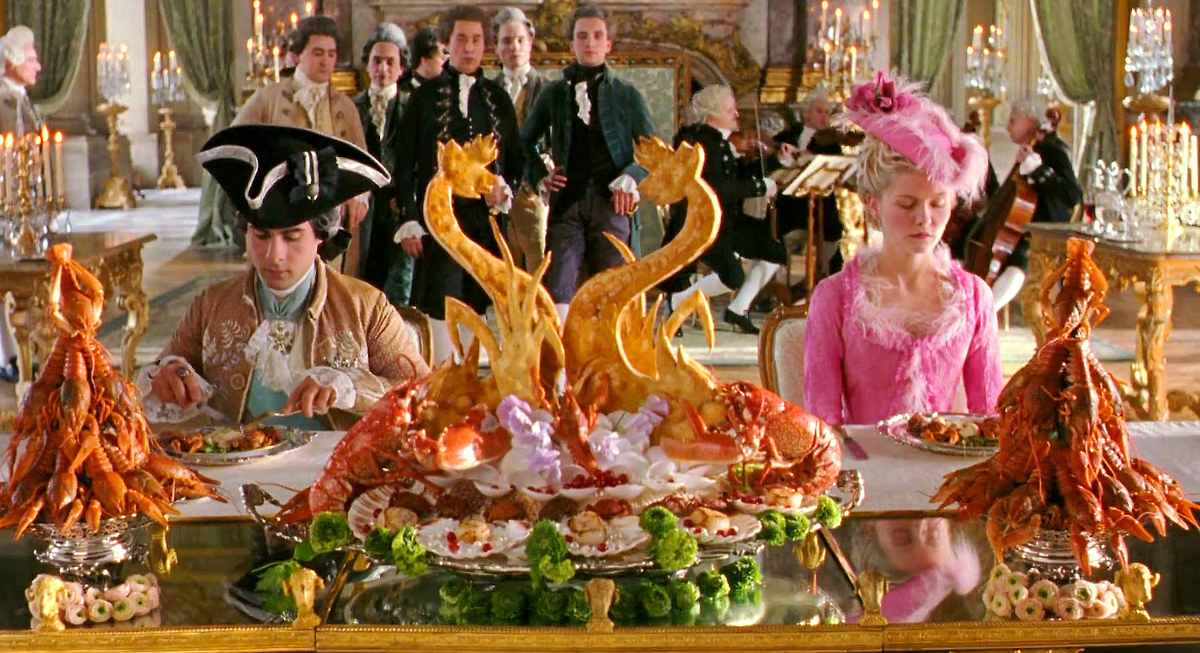

Oysters and Seafood

Credit: flickr

In April 1671, a huge dinner at Château de Chantilly was too much for François Vatel, the famous manager for the Grand Condé. He was planning a three-day party for King Louis XIV, but when the oysters were late, Vatel got so upset that he took his own life.

Poularde de Bresse en vessie

Credit: flickr

Dinner at Versailles often began with something exciting. A special Bresse chicken was filled with foie gras, black truffles, and flavored with Armagnac and Madeira, then cooked in a pig's bladder. As it cooked, the bladder puffed up and kept all the flavors inside. When served, cutting it open released fragrant steam.

Stomachs of Riverside Birds with Sand-leek Sauce

Credit: Getty Images

One of the stranger dishes served at Madame de Pompadour's table was "stomachs of riverside birds with sand-leek sauce." Her chef, Benoît, probably made it more to impress people with rare ingredients than because it tasted good. Finding these unusual items was hard, and the dish showed wealth and extravagance.

Pinot Noir

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

In the 1600s, in the hills of Hautvillers, Dom Pierre Pérignon made wine carefully. He really liked Pinot Noir grapes, cut the vines back a lot to get fewer grapes, and treated each grape like it was precious. The wine became a symbol of high status and appeared on the tables of the most powerful people in France.

Special Spring Water

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Marie Antoinette didn't always indulge in fancy, sparkling drinks or rich foods on gold plates. Sometimes, she just drank water from Ville d'Avray, a small town known for its very clear springs. She would drink it with simple, crisp biscuits and take her time to enjoy them without any formal ceremony.

Brioche

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

In 18th-century France, brioche showed who was rich and who was poor. It was made with lots of butter, eggs, and sugar, something regular villagers couldn’t afford. Even though Marie Antoinette probably didn't say, "Let them eat cake," her love for brioche made her seem disconnected from the struggles of ordinary people.

Croquette

Credit: flickr

Long before you could find croquettes in regular restaurants, they first appeared in the fancy kitchens of King Louis XIV's court. In 1691, François Massialot took a rich stew of meat and vegetables (ragout), put it in a crispy, golden shell, and called it a croquette. These early croquettes often had expensive ingredients like truffles and cream cheese.

Breaded Foie Gras

Credit: flickr

When the French kings were at their most powerful, breaded foie gras turned a luxury food into something even more special. He took a tasty mix of truffles and cream cheese, wrapped it around foie gras, covered it in breadcrumbs, and fried it until it was golden and shiny.

Baba au Rhum

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Nicolas Stohrer, who had trained in Poland, came to France with a dry babka cake and made it amazing. He soaked the cake in wine, layered it with custard and saffron, and added raisins and grapes, creating a rich treat he called "Ali Baba." Over time, the recipe changed to the "baba au rhum," with rum replacing the original wine.

Mille-feuille

Credit: flickr

The mille-feuille, with its light layers of flaky pastry and shiny top, quickly became a favorite of the wealthy nobles. The first version didn't even have cream; instead, it used tart jams like raspberry or apricot between the crispy layers. Finished with a shiny glaze and often decorated with pretty swirls, it was both a delicious dessert and a sign of being wealthy.

Lavish Pumpkin Soup

Credit: pexels

Pumpkins were treated as culinary creations rather than simple vegetables at the royal court. In 18th-century France, aristocratic chefs transformed them into elegant dishes. The pumpkin flesh became a rich, herbed soup, and the hollowed-out shell was roasted until tender and fragrant, serving as the pot as well as the presentation.

Meringue

Credit: flickr

Light and sweet, like the gossip at court, meringue became a common dessert for the French nobles. By the 1700s, the kitchens at Versailles often made it because the royals had a sweet tooth. Some say Queen Marie Leszczyńska brought it from Poland, while others say Marie Antoinette loved it so much she made it herself.

Bouchée à la Reine

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Often not as noticed as the more extravagant things at Versailles, Queen Marie Leszczyńska still left her mark with a dish, not a grand spectacle. The bouchée à la reine—a light puff pastry filled with a creamy mix of chicken, veal, mushrooms, and sometimes small dumplings—was named after her and became a regular dish on the royal table.